By: Krisstina Rao

My journey in social innovation began when I was still in university, where I took up social projects (and set up one of my own too), all the while trying to find what I now call my ‘burning’.

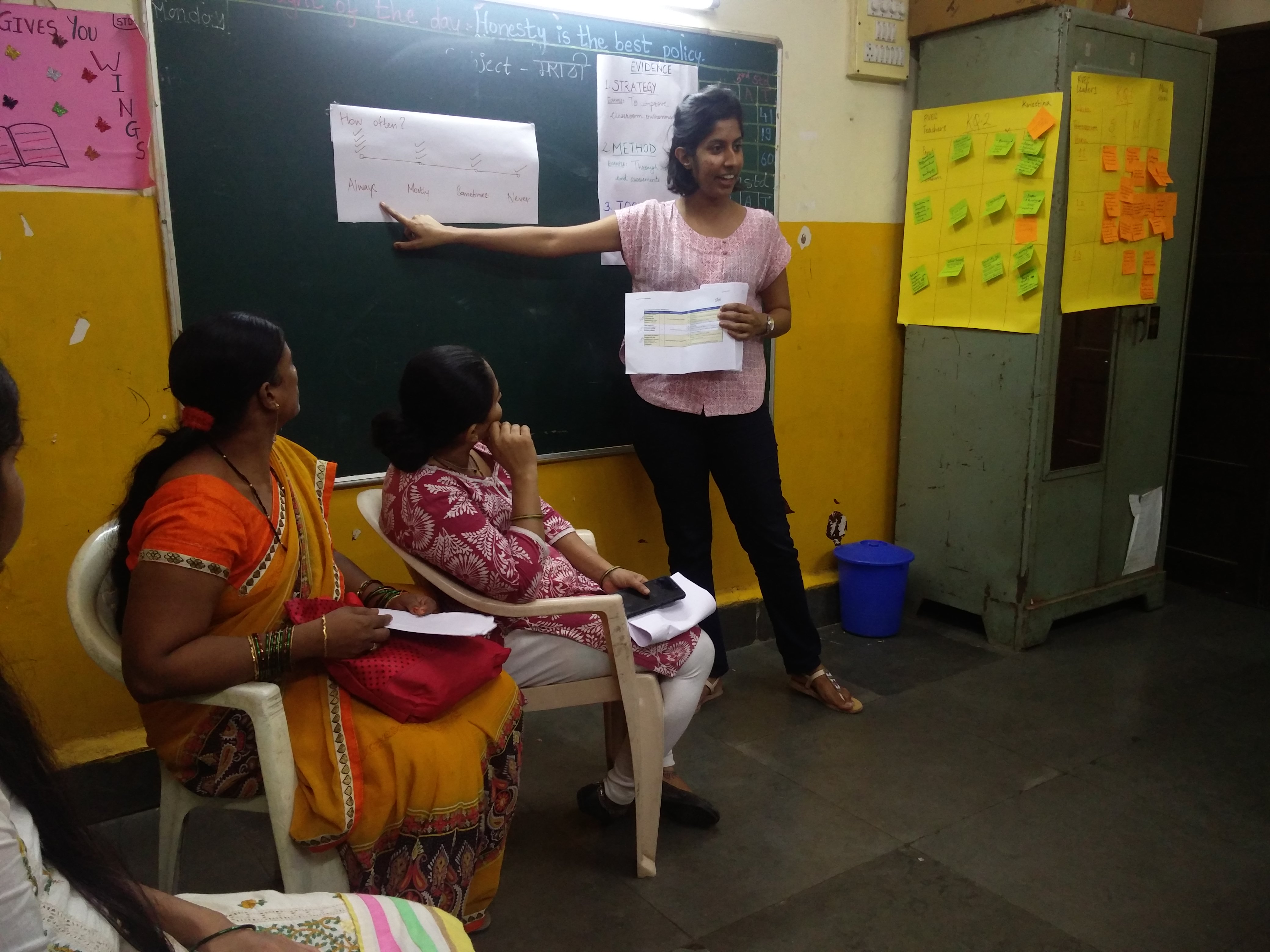

Fast-forward to 5 years later, I lead a social program called Gati (meaning speed or momentum in Hindi), at Atma, which is the accelerator where I work. Gati supports schools to make inclusion for children with disabilities successful. Our team at Atma has been working to build capacity among grassroots educational initiatives– hoping to making them bigger, better and stronger. Nearly a decade into this space, we were confronted with specific challenges in delivery quality education for all children. Some children were left behind, they were excluded or rejected by schools, and never found their way back to a safe and conducive learning environment.

When Gati was set up in Nov 2016, we identified the need to leverage innovation that was already prevalent in the space. While inclusion was far from being realised, there were organisations working tirelessly to making classrooms conducive to students with diverse learning needs, and not only the majority.

The idea was simple:“How might we make resources for diverse learning needs accessible to all schools?”

In a quest to answer this question, my journey brought me to Amani Institute. For someone who had just been introduced to design thinking, I was excited at the opportunity to be able to apply this in the sector of social innovation, but I wasn’t sure of how to use this tool to influence behaviour change!

The Amani’s Social Innovation Framework (ASIF) brings together ideas from design thinking, systems change and adaptive leadership– to allow practitioners in the social sector to truly understand nuances of social problems, and solve for the same.

This tool could not have come at a better time. Gati’s work in making inclusion in education successful had brought us to a place of strategy review. We had identified the gap: the focus on academic achievement in schools, has proven to be detrimental to the unachievers (who were then excluded), but also brought to the forefront concerns about how schools could forter empathy and tolerance– valued that we so needed in the ‘adult world of the 21st century. But schools could not fathom prioritising the need for diversity in the classroom, and we struggled to convince them otherwise.

The ASIF reaffirmed this: the crux of a social problem could not lie with lack of willingness to change mindsets– meaning we had to dig deeper. I’ve had the opportunity since then to go back and forth with testing crucial assumptions we made along the way, which brought me to a crucial insight that we’re testing out now. Including diverse learners is something noble and worthwhile that everyone believes in, in theory. But practically, the onus of including diversity falls on the teachers.

Our work now is gearing towards answering the question: “How might we make inclusion achievable and seem achievable for teachers?”

This continuous reframing and back and forth between design and implementation can get messy, but the iterative nature of the ASIF has helped me identify where my design has been breaking down, and where I should be looking to fix it.

Krisstina Rao is an Amani Fellow from Mumbai, India who completed her immersion phase in Bengaluru. Are you looking to accelerate your career in social impact? Applications are open for our Social Innovation Management Program in Bengaluru, Sao Paulo, and Nairobi!